One of the finest sailors America ever produced was Commander John Newland Maffitt, who began his career in the U.S. Navy. It was not long before he stablished himself as a highly respected officer. Not long after the Confederacy was formed, the U.S. government began secret arrests of those suspected of Southern sympathies. A friend told Maffit that his name was on the list, so he arranged to leave. Commissioned as a Confederate naval officer, one of his exploits paints the picture of this man.

It was August of 1862, and the CSS Florida was in Caribbean waters, Maffitt in command. That morning two of his men were ill, but by sundown more than half the crew was sick with Yellow Fever. Cuba was nearby, and Maffitt managed to make anchor. He wrote in his journal that only three men were able to report for duty: “By this time the quarter-deck had been converted into a hospital, where at all hours of the day and night my presence was required, for there was none to aid, none to relieve me from the exhausting demand upon my medical attention to the sick and dying. The sun rose and set upon the beautiful Florida. At her peak the Confederate flag waved in solemn dignity.”

Two days later Maffitt was giving medicine to his sick men when he was suddenly “seized with a heavy chill, pain in my back and limbs, and dimness of vision.” The captain collapsed with Yellow Fever. A week later he reported that he awakened to see “three somber-looking individuals,” one of whom said, “I am convinced… that the captain cannot survive.” Hearing this, Maffitt replied, “You’re a liar, sir; I have too much to do, and cannot afford to die.”

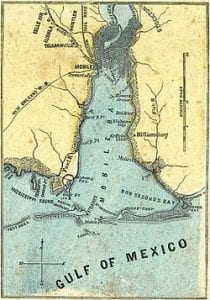

Maffit did survive, and on the 1st of September the Florida left Cuba, on course to Mobile Bay, Alabama. Federal warships were certain to meet him. The Union blockade of the Confederate coastline was known as the Anaconda Plan, after the giant snake, the idea being to strangle the South.

The Florida was so low on supplies that she could not respond with her own guns. Maffit later wrote: “In truth, so terrible became the bombardment, every hope of escape fled from my mind. One gunboat opened on my port bow, the other on our port quarter, and the cannonading became rapid and precise.”

Maffit sent men up the masts to adjust the rigging for best speed, and Florida stormed ahead, shells “bursting over and around us, the shrapnel striking the hull and the spars at almost every discharge.” Many of the men were still ill, including Maffitt, but they had the backbone Blockade Runners were known for, and “everyone acted well his part.” Finally, Maffitt got his ship clear of the encircling Union ships and began to close on the coast and the protection of the guns of Confederate Fort Morgan. “…battered and torn, war-worn and weary, with her own banner floating in the breeze, the Florida in safety is welcomed to her anchorage by hearty cheers from the defenders of Fort Morgan.

Embarrassing as this was for the Union Navy, Maffit poured salt on the wound a few months later when he made his way to sea through the same blockade. In two years of service, the Florida captured or destroyed millions of dollars in Union goods, including fifty vessels captured.

At the end of the war Commander Maffitt refused to surrender his ship, sailing to Britain instead. In 1904 Admiral George Dewey – the only American Admiral to ever wear five stars – referred to Maffitt as “the elite of the Navy, the bravest of the brave.” This was from a man who had fought against Maffitt as a Union naval officer in the Civil war, and who was in command of a U.S. fleet in 1898 that destroyed or captured the entire Spanish Pacific Fleet. High praise, indeed.