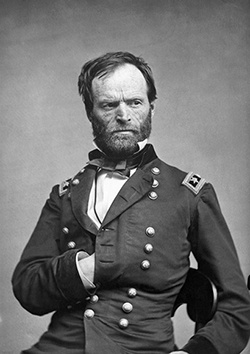

The words below are not gentle. I will keep this short, but be warned: if you think of General William T. Sherman as a heroic man, you may not like what you learn.

Atlanta is now a prosperous city that looks to the future. After all, its symbol is a phoenix rising from the ashes, with the Latin motto, Resurgens, meaning “Rising again.”

But the ghosts of 1864 still talk, so let me tell you why there will never be a statue of Sherman in Atlanta.

Many know of Sherman’s “March to the Sea.” Fewer know that his Special Field Orders No. 120 changed the way war was fought. Previously, civilians and their homes were officially off limits. Cities and personal possessions were generally respected. Not after Sherman’s order. Here is part of it:

“To army corps commanders alone is intrusted the power to destroy mills, houses, cotton-gins, etc.; and for them this general principle is laid down: In districts and neighborhoods where the army is unmolested, no destruction of each property should be permitted; but should guerrillas or bushwhackers molest our march, or should the inhabitants burn bridges, obstruct roads or otherwise manifest local hostility, then army commanders should order and enforce a devastation more or less relentless, according to the measure of such hostility.”

“Otherwise manifest hostility?” “Enforce a devastation more or less relentless, according to the measure of such hostility?” How does one interpret that? Perhaps this will clarify Sherman’s intentions, from one of his 1864 telegrams to Ulysees S. Grant:

“Until we can repopulate Georgia it is useless to occupy it, but utter destruction of its roads, houses, and people will cripple their military resources. … I can make the march and make Georgia howl.”

Grant was already engaged on a campaign of destroying Southern supplies, including food, water, clothing, and transportation. But some historians claim that Special Field Orders No. 120 began a new and “modern” era of warfare, one that has resulted in the loss of countless millions of civilian lives. I would not go so far as to say Sherman alone started it, but his tactics were studied and acted on by later military leaders, even today.

One of Sherman’s officers, John Acheson, helps us understand the effects of Sherman’s “march.” The following quotations are from Acheson’s letters to his parents:

“As for the wealthy planters… nobody sympathized with them in the desolation of their homes, but scores of poor families have I seen, who had had no hand in bringing the present trouble upon the country, left without a mouthful to eat, and not knowing where to turn to get it, or what in the world to do to relive their distress.”

“I have many times heard mothers say that they did not care for themselves if they could only get something for their children to eat; and hundreds of them have come to the General along the march and begged him to let them go with the Army, for if left behind they would surely starve.

“But it is not from legitimate foraging alone that the people suffer. Outrages of every description are committed by the stragglers from our columns. These men know that they can wander off from the column, enter houses and commit whatever depredations they choose without any fear of detection. Dwellings are pillaged – the inhabitants threatened with death, unless they bring forth their money and other hidden valuables; rings and earrings taken by force from persons of women; and outrages of every description perpetrated by men who have slipped away from their commands.”

No doubt things were made worse by some soldiers acting without orders. But once leaders start to act with cruelty, it is only a short trip to “outrages of every description.”

Sherman wrote a two-volume memoir after the war. It contains a number of his orders from the war. It does not contain No. 12. It most certainly does not contain his telegram to Grant. However, I did find things like these:

“…to make a circle of desolation around Atlanta…”

“Heavy fires in Atlanta all day, caused by our artillery.”

“I peremptorily required that all the citizens and families resident in Atlanta should go away.”

“We want all the houses of Atlanta for military storage and occupation.”

Ten year-old Carrie Berry was in Atlanta while Sherman’s army shelled the city. In her diary she wrote of the weeks of shelling. On August 23rd she wrote, “There is a fire in town nearly every day. I get so tired of being housed up all the time. The shells get worse and worse every day. O that something would stop them.” Carrie was nearly killed by the artillery, but she survived, only to be witness to the burning. On November 15th she wrote, “This has been a dreadful day. Things have been burning all around us. We dread to night because we do not know what moment that they will set our house on fire.”

Texas General Hood stood against Sherman in Atlanta. Hood had been commanding men since the beginning of the war, had lost one leg and the use of an arm from battle injuries. He was no stranger to the brutality of war. While negotiating the treatment of civilians in Atlanta, Hood wrote to Sherman:

“And now, sir, permit me to say that the unprecedented measure you propose transcends, in studied and ingenious cruelty, all acts ever before brought to my attention in the dark history of war.”

His scathing messages to Sherman reveal a lot. In one of them he wrote:

“…there are a hundred thousand witnesses that you fired into the habitations of women and children for weeks, firing far above and miles beyond my line of defense.”

Hood, a hardened veteran, recognized the cold glint of evil.

Sherman achieved the status of war hero after the war, but not in the lands where he slashed and burned.

Why are only the losers in war tried for war crimes? Sherman committed major war crimes. He should of been tried and punished for his actions.