Signaled by a cannon’s roar at 5:30 AM, General McDowell’s Union army attacked across a Virginia stream known as Bull Run (a run is a small stream or brook). It was still dark and the green troops had a hard time making their way, but soon the battle was in full rage.

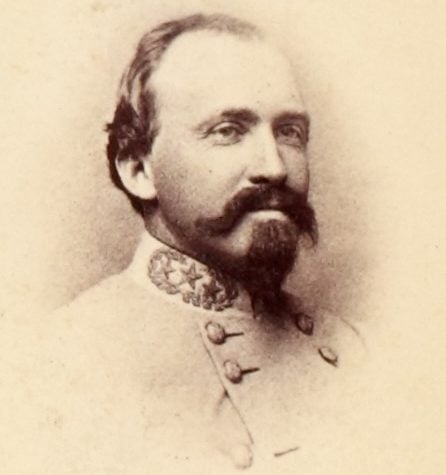

It was July 21st of 1861, in Manassas, Virginia. Confederate General Beauregard was in tactical command of the Southern troops. Advantages went back and forth throughout the day, but General Joseph E. Johnston had brought reinforcements by train and things were looking good. Then, Beauregard saw a column of troops maneuvering to his left. In his own words:

“At their head waved a flag which I could not distinguish. Even by a strong glass I was unable to determine whether it was the United States flag or the Confederate flag. At this moment I received a dispatch from Capt Alexander, in charge of the signal station, warning me to look out for the left; that a large column was approaching in that direction, and that it was supposed to be Gen. Patterson’s command coming to reinforce McDowell. At this moment, I must confess, my heart failed me.”

Confederate Private Carlton McCarthy, a witness to this event, described it in a book he wrote after the war:

“General Beauregard tried again and again to decide what colors they carried. He used his glass repeatedly, and handling it to others begged them to look, hoping their eyes might be keener than his.”

“General Beauregard was in a state of great anxiety…”

The general knew that his men, worn and exhausted from hours of fighting, would not be able to hold out against an additional attack by fresh troops. He wrote:

“I came, reluctantly, to the conclusion that after all our efforts, we should at last be compelled to yield to the enemy the hard fought and bloody field.”

Beauregard instructed one of his officers to go to the rear and inform Gen. Johnston to prepare reserves to support the retreat. But just as the officer turned to go, Beauregard told him to wait:

“I took the glass and again examined the flag. … A sudden gust of wind shook out its folds, and I recognized the stars and bars of the Confederate banner.”

Private McCarthy described it this way:

“Suddenly a puff of wind spread the colors to the breeze. It was the Confederate flag – the Stars and Bars! it was Early with the twenty-fourth Virginia, the Seventh Louisiana, and the Thirteenth Mississippi… Beauregard turned to his staff right and left, saying ‘See that! The day is ours!’ and ordered an immediate advance.”

The flag Beauregard recognized was the Confederate First National Flag, at the front of Colonel Hay’s 7th Louisiana Volunteers. The 7th was part of Jubal Early’s brigade that was launching an attack on the Union flank. Early’s attack helped turn the tide, and the First Battle of Manassas ended in a resounding Confederate victory.

Streams of Union soldiers began racing to the rear, many of them rushing by Congressmen, reporters and other onlookers who had come to picnic and watch the rebels be defeated. Only now the Federals were in rapid and disorderly retreat to Washington, only 25 miles distant.

Beauregard’s uncertainty could have proved pivotal, but confusion about the flags was widespread on both sides. Thirteen years later General Johnston wrote these words:

“It was generally believed by those with whom I was in the habit of conversing, just after the battle of Manassas, that some of the Federal regiments bore Confederate colors in the action, and Northern papers contained similar accusations against us.”

The truth was that Southerners had a deep attachment to George Washington and the flag their fathers and grandfathers had adopted. As a result, the national flag of the Confederacy was strikingly similar to the Union Stars and Stripes.

Both Union and Confederate troops were plagued by this problem. A solution was needed, and Beauregard put things in motion that would make history: the creation of the Confederate Battle Flag. In Part II of this story the flag design and approval will unfold.

Love it, stated Southern an true

Love it, stay Southern an true my southern friends

Deo Vindice!